In the last chapter, we already mentioned that genes can contain different versions of the same "recipe". However, although our chromosomes are somewhat like a cookbook, we, of course, can't actually find written instructions in them. So, how do we read DNA and what is genetic variation exactly?

DNA

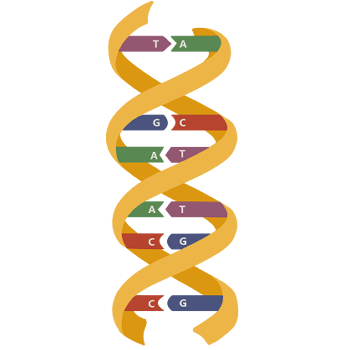

Our genes are made up of DNA. Two strands of DNA are coiled around each other to form a "double helix" shape. These DNA strands are composed of 4 different building blocks: the bases A (adenine), T (thymine), G (guanine), and C (cytosine) - don't worry, you don't have to remember their full names. These four letters are essentially the alphabet of our genes. Recipes for proteins are written in different sequences of A, T, G and C.

The different bases attach to each other - A always to T, and G to C. This way, the 2 DNA strands get connected. It would look something like this:

This is pretty neat because it means we can read the DNA sequence from either strand, and the result is the same. But how do we read these sequences then, and how do only four letters translate to so many different proteins?

Codons

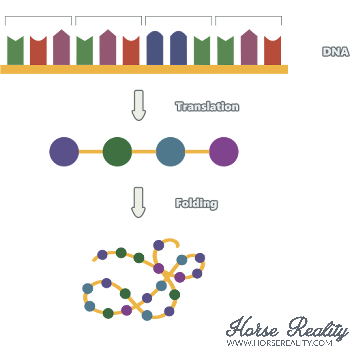

DNA uses three-letter "words", called codons, to mean different things. So, we can read a DNA sequence separated into triplets like CTA - GGC - CAG, etc. These codons translate to, in total, 20 different amino acids. The codons "CAG" and "CAA", for example, translate to the amino acid glutamine.

Amino acids are, in turn, the building blocks of proteins. A protein is made up of many - hundreds, or even thousands - of amino acids. The final shape, function and characteristics of a protein all depend on having the right amino acids (and, consequently, DNA!) in the right order.

But, on a long strand of DNA, how do we know where a gene starts and ends and where we should start reading? Our DNA also has certain "start" and "stop" codons, which let our body know where it should start and stop translating a part of DNA.

DNA sequence -> Amino acid chain -> protein

Mutations

Our body normally does a very diligent job to protect our DNA from damage and to check for mistakes, for example, when it makes copies to pass on to offspring. But mistakes can happen, and some letters can be changed to others, or letters can be added or removed. These changes are called mutations.

Types of mutations:

Point mutation: One letter is affected

Insertion: One or more extra letters added into the DNA

Deletion: One or more letters removed from the DNA

Substitution: A letter is replaced by a different one

Inversion: A piece of DNA is flipped, reversing the letter order

Duplication: A piece of DNA is duplicated

Translocation: A piece of DNA is moved to a different place

Mutations can be neutral, harmful, or create a completely new end product. If the codon "CAG" is changed to "TAG", for example, it is now a stop codon. Our protein will be cut short, and probably won't be functional.

Types of mutations:

Silent mutation: No effect

Missense mutation: A codon is changed to a different one

Nonsense mutation: A codon is changed to a stop codon

Frameshift mutation: A shift in the grouping, or reading frame, of codons

Loss-of-function mutation: The resulting protein has little to no function

These mutations lead to different variations of genes or recipes. These variations are called alleles.